THE GREAT UTOPIA OF HENDRIK CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN

At the Flaminio district in Rome, the museum-home of a visionary Norwegian artist

photographs and text by Massimo Pacifico

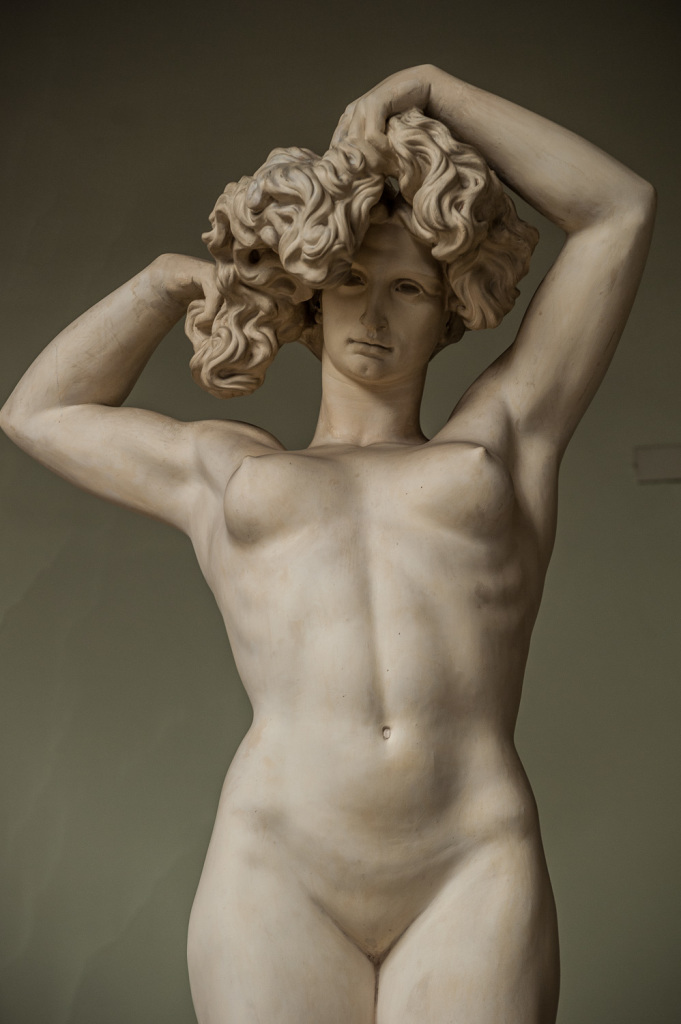

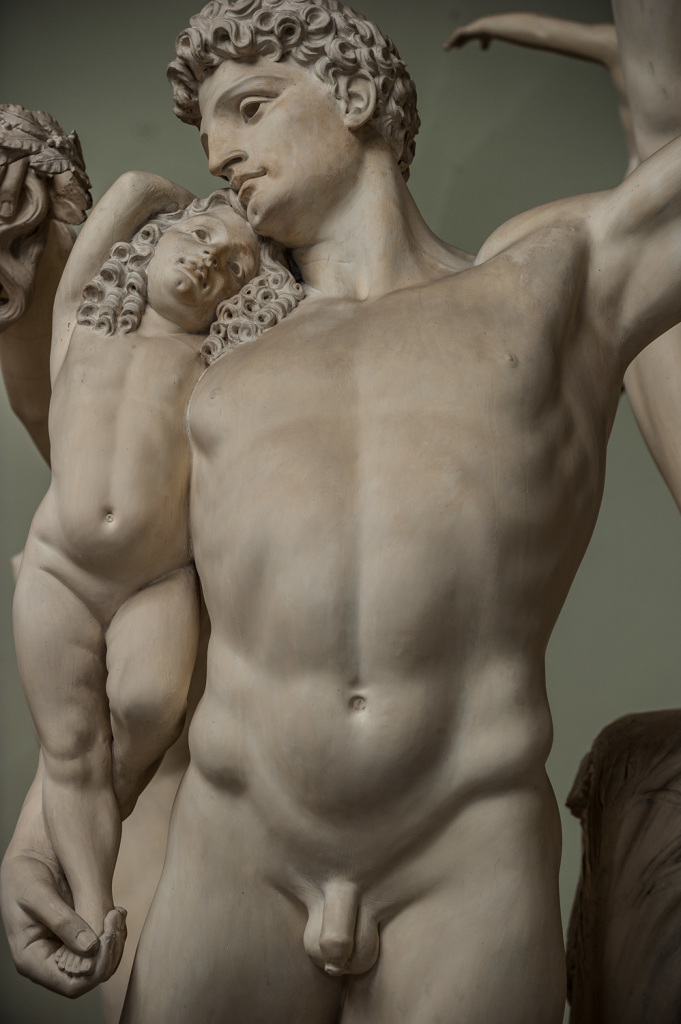

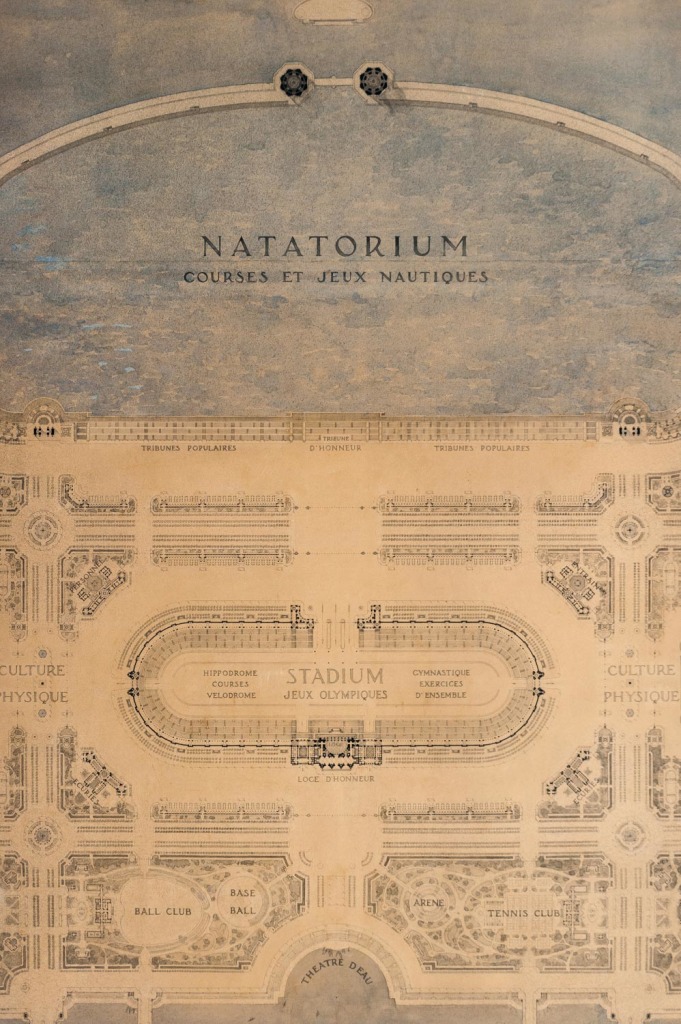

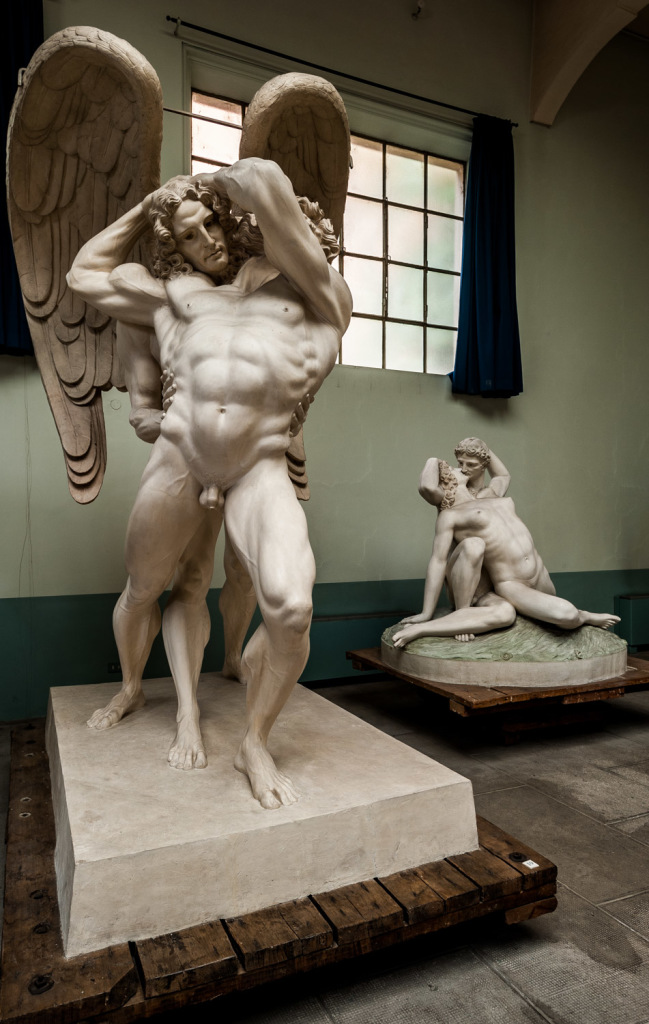

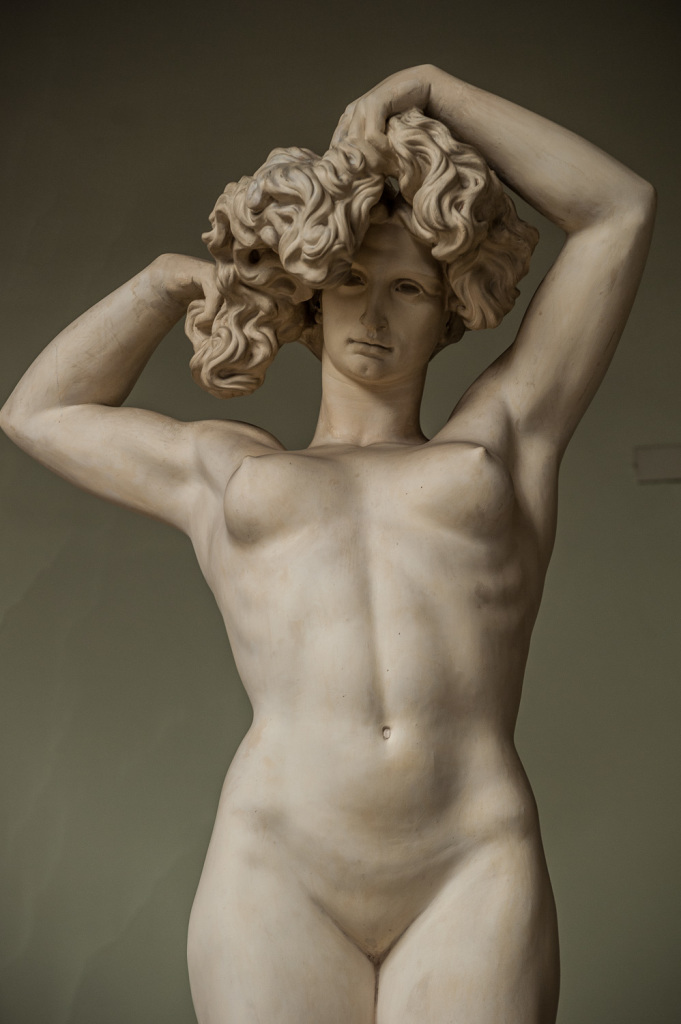

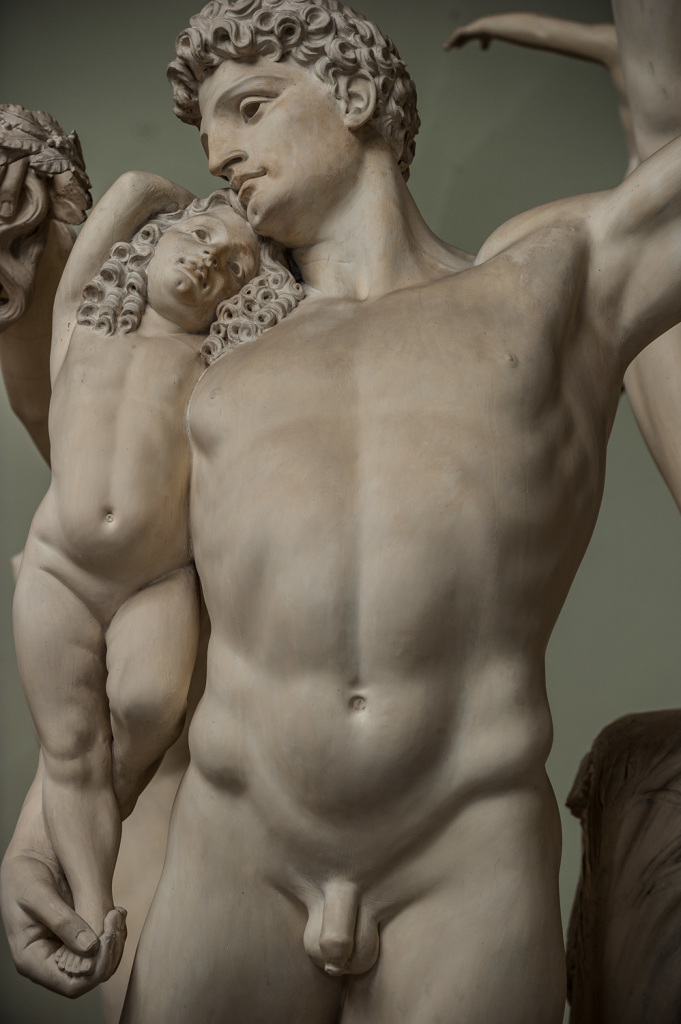

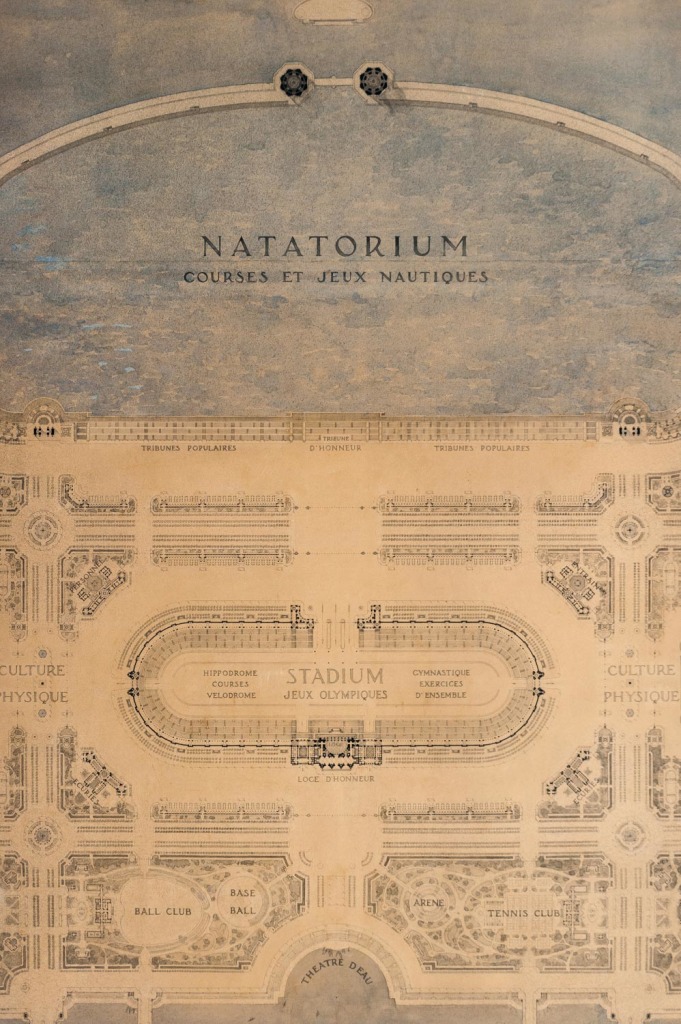

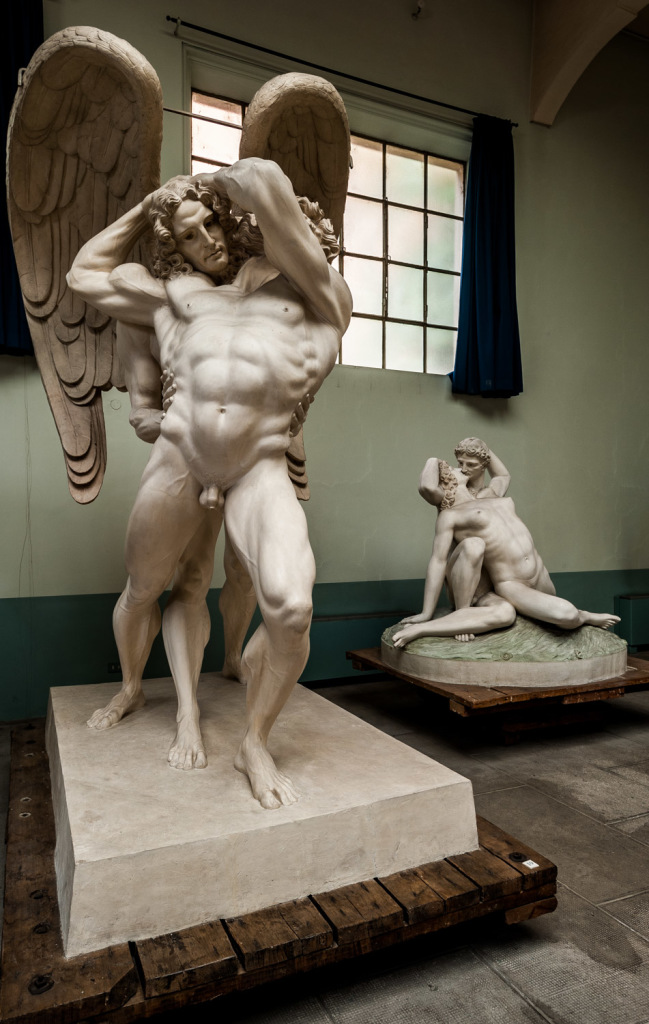

The Norwegian artist Hendrik Christian Andersen (Bergen, 1872 • Rome, 1940) lived in Rome from the late 19th century until his death. From 1922, in the Palazzina Hélène, a pink building that he conceived and decorated in eclectic neo-Renaissance style. On the ground floor of the house two large workshops with the works of the artist are situated. On the first floor was his home, now used for temporary exhibitions devoted to foreign artists. The collection of works (over two hundred sculptures of large, medium and small plaster and bronze, over two hundred paintings and over three hundred graphic works) is remarkable for its exceptionality, being almost entirely centered on the utopian idea of a great “World city”, destined to be the international headquarters of a perpetual laboratory of ideas in the field of arts, sciences, philosophy, religion, and physical culture.

Hendrik Christian Andersen’s reputation in Rome at the beginning of the twentieth century was controversial. Nobody, however, doubted that the Norwegian was a visionary. Already in 1913 he had completed his project for an ideal city. He had designed the maps, made the plastics and forged the sculptures that would adorn it. He had called it World City. With the money of Olivia Cushing, a wealthy American from Rhode Island who was the widow of his deceased brother Andreas (the marriage lasted only two months), he illustrated it in the smallest details in a volume weighing more than five kilograms. An enormous book, which Andersen sent over the years to many heads of state to convince them to build his Eden in their countries for the peaceful development of humanity. None of the powerful took him seriously. Not even the Cavalier Mussolini, who,even though interested, in the meantime engaged his resources in other projects of imperial grandeur .

When, in the early 1920’s, the mansion where the artist intended to convey his illusions took shape, Olivia, who had followed her brother-in-law from New England to Rome, and had funded the building, had been dead for 5 years. Hendrik thus dedicated it to his beloved mother, Hélenè.

The home address of Andersen (via Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, 20) was in the travel carnet of many illustrious characters. More or less frequent attendants were: the comic Ettore Petrolini; the Bengali philosopher Rabindranath Tagore (Nobel Prize in 1913); the intrepid commander of the unfortunate expedition to the North Pole Umberto Nobile; the scientist Guglielmo Marconi (Nobel Prize in 1909); the poetess Sibilla Aleramo; the art critic and dealer Bernard Berenson and his fond customer from Boston, Isabella Steward Gardner; the US magnates Whitney and Vanderbilt. Even the relationship between Andersen and the prolific American-born English writer Henry James had been intense before the villa Helénè was built. Henry and Hendrik had known each other since 1899, and they actually only saw each other seven times before the writer died in 1916 but exchanged 77 letters (at least this many survived Cushing’s moralistic censorship) full of intimate stories and expressed desires.

Today, spending time in the building is no longer a privilege reserved for artists and billionaires. Having become the property of the Italian government in 1978, it is run by the National Gallery of Modern Art and is open from Tuesdays to Sundays from 9.30 to 19.30. Entry is free.

Villa Helene agli inizi del XX secolo

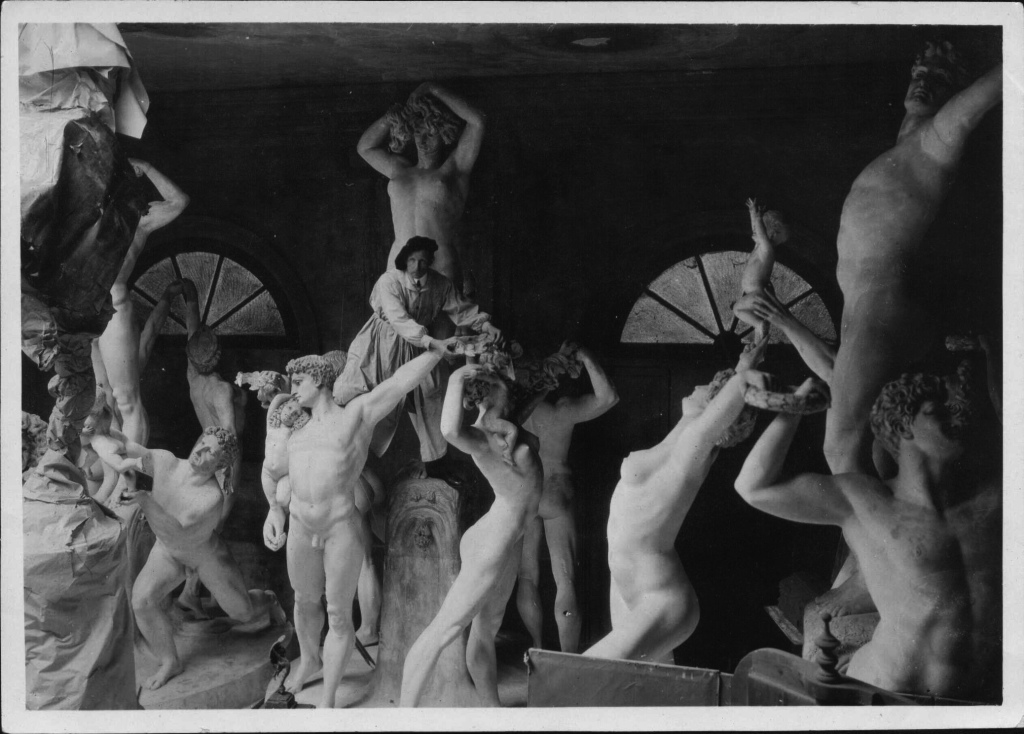

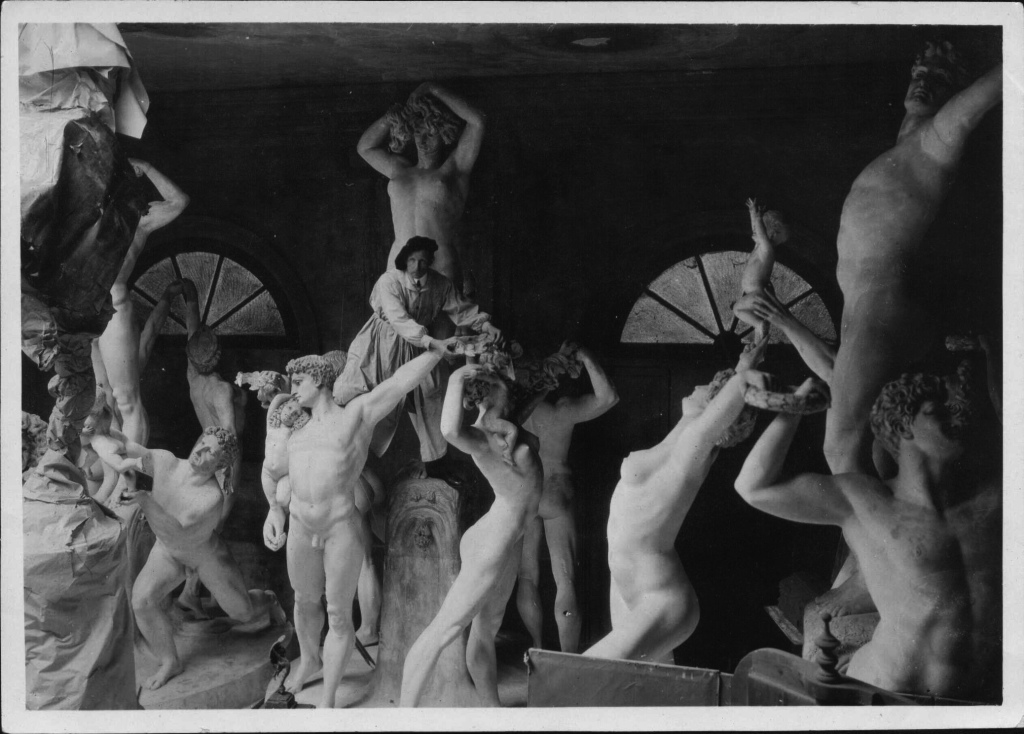

Andersen nel suo studio

Andersen con Herny James