THE BEGINNING

Florence, February 1865: The female college of the SS. Annunziata leaves the location in the former monastery of the Holy Conception, in via della Scala, having been just destined to the functions of the Ministry of Public Works of the new capital of the Kingdom of Italy, and moves to the Villa del Poggio Imperiale, former noble residence of the Medici and Lorraine and starts a new life.

The birth of Italy’s most famous laic and public college, established by decree of the Grand Duke Ferdinando II, in fact dated back to 1823, but only two years later did the first nine college students arrive, with their linen trousseaux, shirts and skirts in combrik and riscendoc, their corsets, the fichu, the cloak, black aprons, blue gloves in silk and wool, black mittens, booties, summer and winter hats for walks and for the garden.

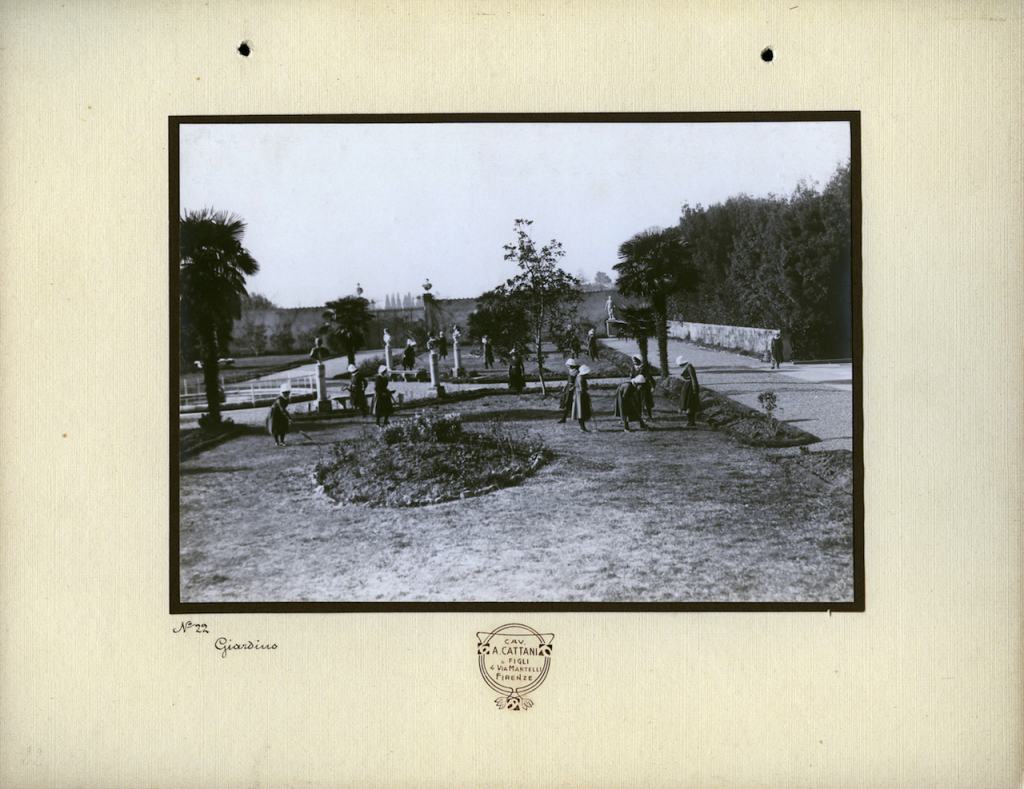

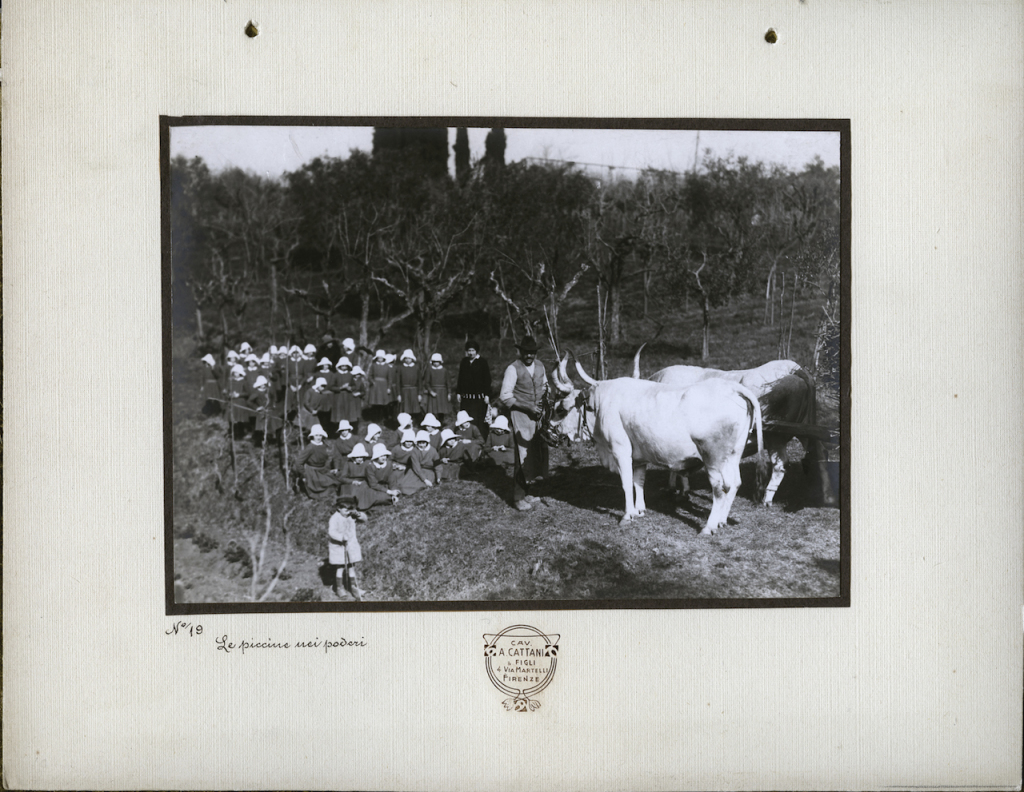

The soul behind the project was the Marquis Gino Capponi, then thirty years old, a politician, fine intellectual and historian of imprint of post-Enlightenment with many and fertile contacts throughout the continent. The nobleman longed for an institute run with liberal ideas, destined to the future women of Europe, to whom impart modern education and not impose any religious faith. The relationship with the city, in the early decades of the history of the Institute, were not idyllic, and again in the spring of 1861, the newspaper La Nazione rages against “the aristocracy seedbed” directed by the Austrian Jenny Plundre Marion. Then the contrasts with the young kingdom attenuated and, while teachers and directors swore allegiance to the King, in the school curriculum of the boarders the new models of the middle-class woman are prefigured: alongside the traditional disciplines, disciplines until then forbidden to female education were introduced such as the sciences; history, especially contemporary; gymnastics; and sports such as tennis, cricket, the ball, and even hunting and fishing and horse riding; gardening and practice of agriculture and animal breeding; art and music; dance, drama and singing; foreign languages; domestic management and opened avanguard laboratories of chemistry and physics, useful for experimental verification of concepts learned in the classroom.

TWENTIETH CENTURY: FIRST ACT

Entering the new century, the life of the college was conditioned by the dramatic events of the time. In the years of the Great War, the left side of the villa, including the chapel, even hosted a military hospital. At that time – it was the spring of 1917 – the princess Maria Jose of Belgium entered the college, at only just eleven years old. Intolerant to harsh discipline and very lively, she was destined to become the wife of Umberto II of Savoy and the last Queen of Italy.

Other important appearances follow one another in the years of Fascism: Edda, Mussolini’s eldest daughter, is recorded among the boarders. She did not resist more than a year. She could not stand to be treated like the others, she was the daughter of the leader, who, however, like all parents, was barred from entering the college. Reliable sources report that even when Mussolini came to take her away, he was greeted without honors and kept waiting for some time. Dark times were announced: the director from Trieste, Maria Patrizi, guilty of not having allowed the boarders to listen to the radio at dinner time while Mussolini proclaimed the birth of the Empire, was removed from office. The new director, Rosa Scopoli, impressed a new explicit fascist character upon the life of the school and soon was able to boast proudly: “Not only the pupils, but also the staff and teachers are permeated by fascist spirit and strong feelings of being Italian”. An internal memo for staff and boarders, meanwhile, required that within the walls of the villa the courtesy form of “she” be abolished only to be replaced with “you”, while the uniforms of “small Italians” and “daughters of the wolf”, during public demonstrations , appeared next to the historical ones of the college.

The life of the boarders, within the walls of the Villa Medici, was marked by rigid schedules for each activity: the wake-up call at six, six thirty or seven o’clock, depending on the season; lessons from nine to twelve; then lunch and recreation in the garden, in the woods, in the courtyards or in the halls. Classes resumed in the afternoon from three to five o’clock; then the piano, singing and harp lessons; and after seven-thirty dinner it was time of the conversation in foreign languages. The day ended with the nine-thirty prayer and a well earned rest in the dormitories, amongst the rococo stuccos and frescoes.

Meals were simple and nutritious: coffee and milk in the morning, which could be replaced by coffee and egg; or broth with egg. At lunch , generally, a soup was served, two meat dishes with vegetables, eggs and fish on the “lean” days, fruit or dessert. Similar was the dinner, but with a more frugal second course.

When the threshold of the Second War arrives, also at Poggio the food becomes scarce, though, thanks to the vegetable gardens, livestock, poultry, rabbits, bees, even in those hard years the girls were able to eat three times a day . In March 1942, a middle school girl wrote in her diary: “Other odors! That pungent one of the soup filled the refectory, and that of the vegetables and strips of meat that often ended up in the pockets of the large aprons … the sour smell of the excrements of a small herd of bunnies mingled with delicate one, of the wallflowers in a tiny piece of land miraculously budding”.

Then came the bombings at the Villa, just as a bomb shelter for over two hundred people was being built; the school was also opened to daily girls, to enable Florentine girls to attend courses. And, as history knows no obstacles, from September to October of 1943 the villa was occupied by the German air force and, in 1944, the Americans also tried to establish themselves in the now deserted and dilapidated location, inhabited by only two boarders who had remained in the college because of family misfortunes.

Then came the bombings at the Villa, just as a bomb shelter for over two hundred people was being built; the school was also opened to daily girls, to enable Florentine girls to attend courses. And, as history knows no obstacles, from September to October of 1943 the villa was occupied by the German air force and, in 1944, the Americans also tried to establish themselves in the now deserted and dilapidated location, inhabited by only two boarders who had remained in the college because of family misfortunes.

TWENTIETH CENTURY: SECOND ACT

In the after-war fervor, the College is repopulated, and new students arrive, sometimes foreigners or daughters of Italians living abroad, sometimes daughters of former partisans or those whom had struck fortune with the war, in the historic halls orphans of war and daughters of aristocrats and bourgeois coexist. Life at the Poggio resumes its normal course. A centralized radio is installed, a small “ape” truck is bought to bring the grocery shopping to the kitchens, the infirmary is expanded, spaces devastated by grenades are restored. The school is open to collaboration with praiseworthy associations, from the “Red Cross” to the “Company of animal protection.” During the annual charity fair, the boarders sell their handicrafts: embroidery, ceramics and paintings. The direction is uncompromising about discipline, order and punctuality: so the pupils can browse magazines like Oggi, but only after an appropriate censorship. They practice many sports, from fencing to skating, the javelin and riding. And no less attention is devoted to manual work and outdoor activities on farms. In particular, musical education, imparted during the entire school curriculum, and focuses on repertoire ranging from classical to folk.

The uniform is complex: the girls wear a “pocket” in white cotton over their petticoat, the collar, and then, the uniform, the black apron, fastened at the back, a pleated skirt with an opening that allows one to stick their hand in to get to the pocket. And finally, a white belt and a big bow behind, in different colours, which distinguishes the pupils for their courses: green for the elementary and middle school; red and blue for the high school.

The postwar period saw the steady increase of the educational proposals and the number of boarders. And the initial school, divided in 1945, the opening of a kindergarten in 1952 followed. The central heating enters the institute, in its dormitories, classrooms and monumental halls, and life becomes more comfortable and modern at the Poggio. New paths of study are set up, such as a modern linguistic high school in 1960 and, in the aftermath of the 1968s, even within the walls of the Villa Medici, something changes in the rhythms of life and daily habits, with the birth of the new Scientific high school; Then in 1994, a course of experimental studies is established: the European classical studies, still in vogue.

The postwar period saw the steady increase of the educational proposals and the number of boarders. And the initial school, divided in 1945, the opening of a kindergarten in 1952 followed. The central heating enters the institute, in its dormitories, classrooms and monumental halls, and life becomes more comfortable and modern at the Poggio. New paths of study are set up, such as a modern linguistic high school in 1960 and, in the aftermath of the 1968s, even within the walls of the Villa Medici, something changes in the rhythms of life and daily habits, with the birth of the new Scientific high school; Then in 1994, a course of experimental studies is established: the European classical studies, still in vogue.

TODAY

Thanks to the work of the Foundation Memofonte now, on the Poggio Imperiale website, this story of a recent past is available on-line, and, thanks to a computerized archive, it will be possible to reconstruct the history of the many boarders who lived and studied in the college, from 1825 onwards.

But another activity now distinguishes the life of the school: since two years a group of volunteer students of the Liceo study and prepare to acquire the driving license of the Villa Medici and its treasures. The virtual journey begins backwards from the Napoleonic age, when Elisa Baiocchi’s trusted architect, Giuseppe Cacialli, founder of Tuscan neoclassicism intervenes on the already neoclassical facade, elevates the porch of one floor, covers the loggia of the peristyle, draws the pediment with the great central clock and two winged Victorias. He also builds the two lateral structures, the beautiful neo-classical chapel on the left, the guards on the right. Indeed, the origins of the villa date back to the early Renaissance, when the “master’s house” of Peter Baroncelli passes to the Pandolfini, then to the Salviati and then enters among the assets confiscated by Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1564. It is taken care of by Isabella, the educated daughter of Cosimo, who here gathers their collections of art and the first group of ancient statues. But one must wait for 1624 because the villa acquires the importance and the title of “Imperial”, by the will of Maria Maddalena of Austria, wife of Cosimo II de ‘Medici, who, with the Grand Ducal edict, emphasizes the identity of the Villa as palace of the reigning power of the sister of Emperor Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria and future representative location of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany. Poggio Imperiale did certainly not form the melancholy retreat for the widow of the late Grand Duke, but was, instead, a comfortable and elegant suburban villa close to the city, where she could devote herself, away from the officiality of the court, to the otium and the pleasures of art and life in the countryside. Since that time the Villa became in fact the residence symbol of the Medici women, a true extension of the court, not less magnificent than the Palazzo Pitti.

But another activity now distinguishes the life of the school: since two years a group of volunteer students of the Liceo study and prepare to acquire the driving license of the Villa Medici and its treasures. The virtual journey begins backwards from the Napoleonic age, when Elisa Baiocchi’s trusted architect, Giuseppe Cacialli, founder of Tuscan neoclassicism intervenes on the already neoclassical facade, elevates the porch of one floor, covers the loggia of the peristyle, draws the pediment with the great central clock and two winged Victorias. He also builds the two lateral structures, the beautiful neo-classical chapel on the left, the guards on the right. Indeed, the origins of the villa date back to the early Renaissance, when the “master’s house” of Peter Baroncelli passes to the Pandolfini, then to the Salviati and then enters among the assets confiscated by Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1564. It is taken care of by Isabella, the educated daughter of Cosimo, who here gathers their collections of art and the first group of ancient statues. But one must wait for 1624 because the villa acquires the importance and the title of “Imperial”, by the will of Maria Maddalena of Austria, wife of Cosimo II de ‘Medici, who, with the Grand Ducal edict, emphasizes the identity of the Villa as palace of the reigning power of the sister of Emperor Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria and future representative location of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany. Poggio Imperiale did certainly not form the melancholy retreat for the widow of the late Grand Duke, but was, instead, a comfortable and elegant suburban villa close to the city, where she could devote herself, away from the officiality of the court, to the otium and the pleasures of art and life in the countryside. Since that time the Villa became in fact the residence symbol of the Medici women, a true extension of the court, not less magnificent than the Palazzo Pitti.

And it is the architect Giulio Parigi that enlarges the villa, builds to the west the section for the Grand Dukes while the interventions of decoration are entrusted to the leader of the seventeenth-century Florentine painting, Matteo Rosselli, and his workshop: here is the cycle of frescoes dedicated to the biblical heroines, the empresses and queens, the virgin martyrs, real history in gender pictures.

And it is the architect Giulio Parigi that enlarges the villa, builds to the west the section for the Grand Dukes while the interventions of decoration are entrusted to the leader of the seventeenth-century Florentine painting, Matteo Rosselli, and his workshop: here is the cycle of frescoes dedicated to the biblical heroines, the empresses and queens, the virgin martyrs, real history in gender pictures.

The season of Mary Magdalene is followed by Vittoria della Rovere, wife of Grand Duke Ferdinando II de ‘Medici, who brings the great art treasures of the Urbino family to Florence, now in the Uffizi; Victoria intervenes in the Villa del Poggio Imperiale by expanding architecture with the changes signed by Pietro Tacca in the entrance courtyard, then with the Throne Room, today the refectory of the college, sumptuously frescoed by the Roman painter Francesco Corallo. After the extinction of the Medici family with “the inept and idle Giangastone” – as him defines Matteo Marangoni in the first monograph devoted to the Poggio – it is 1765 when the eighteen year old Peter Leopold of Lorraine becomes the new Grand Duke of Tuscany, falls in love with the Poggio Imperiale and builds apartments on the first floor, the ballroom, constructs the extraordinary Chinese quarters with bold wallpaper of exceptional beauty and chinoiserie of all kinds, gives the villa the enlightenment decorum of a modern European court, adorned with grace inspired by the French rococo in private settings while those for official meetings are decorated with cultured and noble neoclassical taste . And on the ground floor, Pietro Leopoldo asks the architect Gaspare Maria Paoletti to realize the great outdoor space leading to the garden, entertainment and representation rooms full of light, decorated with forest landscapes, hunting scenes, trompe l’oeil porches, and to represent mythological characters and wild figures; to the famous Prince’s secretariat, with frescoes dedicated to the theme of Good Government: there the Tuscan Enlightment, ministers of state were greeted, and there, it is said, the abolition of the death penalty was signed, for the first time in history.

Today’s students live every day in these environments with a sense of belonging that emerges from the first months of study. The rhythms, patterns, lifestyles, the orientations are those of a normal lower and upper secondary school of the Italian state in 2015. However, what is perceived is the awareness of living in a place full of artistic and highly valuable testimony of many individual and collective stories that within those walls have marked one hundred and fifty years of Italian school.