Comiso, July 20th, 1943. It’s been ten days since the landing of American troops on the southern coast of Sicily, and just over four will have to elapse before the arrest and the fall of Mussolini.

The war is a frightening scenario, documented by millions of photos taken by military photographers or by the photojournalists following the large armies. So wide was the theater of the Second World War, as is the extraordinary photographic documentation that remains. Consider that only in the Red Army there were more than three hundred photographers dead at the front. Their total number, among military photographers and photojournalists, is of thousands.

But, however, these testimonies are complex, ambiguous: often snapshots are “built” photos, halfway between propaganda and documentation. They are images of the winners to go around the world on the front pages of the great illustrated weeklies: the Marines hoisting the American flag at Iwo Jima (the photographer was Joe Rosenthal), or the Soviet soldier waving the red flag with the sickle and the hammer on the facade of the Reichstag in smoking Berlin (photo by Yevgeny Khaldei).

These are tragic photos, taken in the aftermath of decisive victories, of bloody advances, with enormous losses. As there are also, result of German thoroughness, the terrible images of the “cleansing” of the Warsaw ghetto taken by Jürgen Stroop.

The view that appears in the first photo of the countryside of Italy is that of a less bloody war. The Operation Husky does not find, on the southern shores of Sicily, the same resistance that, months later, the Normandy invasion will.

It is a primitive and rural Italy documented by Phil Stern, by Robert Capa, by Margaret Bourke-White: donkey carts, farmers that show the way, cities celebrating the arrival of the Allies, physical types of ‘”Southern Italian”, black hair and mustache.

Seen from the south, before September 8th, Italy does not yet know about the partisans hanged with wire and the destroyed cities. It is a view, however, where the spoils of the defeated fascism are always present: skeletons of sunken ships, overturned tanks, arrogant graffiti on the walls.

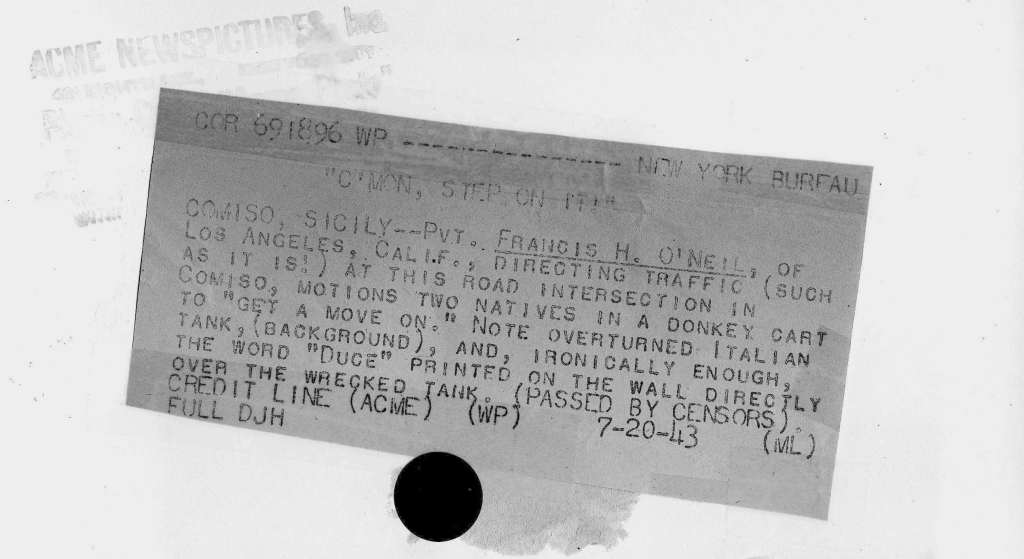

Of this photo we know a lot, if not everything: the title (“Dai! Muoviti”), the date (prior to 20th July 1943), the place (Comiso) and also the name of the soldier portraited. And we also know that the photo passed the censorship of war. The caption on the back says: “The soldier Francis H. O’Neil of Los Angeles (California) directs traffic in an intersection of Comiso and spurs two natives in a cart pulled by a donkey urging them to “get a move on”. One can note in the background an overturned tank and, ironically, the word Duce written on the wall just above the overturned tank”. The author remains unknown, among the many who worked for ACME NewsPictures, a photojournalism company acquired by United Press in 1952, whose archives are now owned by Corbis Images.